Manuscript Illumination

400 to 1435

The codex, our common form of book with folded pages and bound cover, became widespread in the third century AD. The codex tradition was well established by the Carolingian and Byzantine period.

According to art historian Clive Bell "In ages of great spiritual exaltation the barrier crumbles and becomes, in places, less insuperable. Such ages are commonly called great religious ages: nor is the name ill-chosen. For, more often than not, religion is the whetstone on which men sharpen the spiritual sense. Religion, like art, is concerned with the world of emotional reality, and with material things only in so far as they are emotionally significant. For the mystic, as for the artist, the physical universe is a means to ecstasy. The mystic feels things as "ends" instead of seeing them as "means." He seeks within all things that ultimate reality which provokes emotional exaltation; and, if he does not come at it through pure form, there are, as I have said, more roads than one to that country. Religion, as I understand it, is an expression of the individual's sense of the emotional significance of the universe; I should not be surprised to find that art was an expression of the same thing. Anyway, both seem to express emotions different from and transcending the emotions of life. Certainly both have the power of transporting men to superhuman ecstasies; both are means to unearthly states of mind. Art and religion belong to the same world. Both are bodies in which men try to capture and keep alive their shyest and most ethereal conceptions. The kingdom of neither is of this world. Rightly, therefore, do we regard art and religion as twin manifestations of the spirit; wrongly do some speak of art as a manifestation of religion."

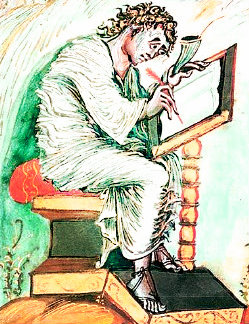

Throughout Christendom, the art of manuscript illumination flourished from the Early Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Manuscript Illumination started around the first century AD and is related to Egyptian papyrology (the art of ancient writing and painting on papyrus). The pages of the books were made out of goat or sheep skins - called parchment or vellum. According to Medieval historian, Julia De Wolf Addison, "The pigments used in Byzantine manuscripts are glossy, a great deal of ultramarine being used. The high lights are usually of gold, applied in sharp glittering lines, and lighting up the picture with very decorative effect. In large wall mosaics the same characteristics may be noted, and it is often suggested that these gold lines may have originated in an attempt to imitate cloisonné enamel, in which the fine gold line separates the different colored spaces one from another. This theory is quite plausible, as cloisonné was made by the Byzantine goldsmiths."

The early manuscripts were copied and embellished in monastic centers, called scriptoriums. The most original and innovative works were created in the British Isles during the seventh and ninth centuries. Accoring to author Julia De Wolf Addison "The work of each scriptorium was devoted first to the completion of the library of the individual monastery, and after that, to other houses, or to such patrons as were rich enough to order books to be transcribed for their own use. The library of a monastery was as much a feature as the scriptorium. The monks were not like the rising literary man, who, when asked if he had read "Pendennis" replied, "No—I never read books—I write them." Every scribe was also a reader. There was a regular system of lending books from the central store. A librarian was in charge, and every monk was supposed to have some book which he was engaged in reading "straight through" as the Rule of St. Benedict enjoins, just as much as the one which he was writing. As silence was obligatory in the scriptorium and library, as well as in the cloisters, they were forced to apply for the volumes which they desired by signs. For a general work, the sign was to extend the hand and make a movement as if turning over the leaves of a book. If a Missal was wanted, the sign of the cross was added to the same form; for a Gospel, the sign of the cross was made upon the forehead, while those who wished tracts to read, should lay one hand on the mouth and the other on the stomach; a Capitulary was indicated by the gesture of raising the clasped hands to heaven, while a Psalter could be obtained by raising the hands above the head in the form of a crown. As the good brothers Page 330 were not possessed of much religious charity, they indicated a secular book by scratching their ears, as dogs are supposed to do, to imply the suggestion that the infidel who wrote such a book was no better than a dog!"

After several centuries the monks became slipshod and careless when transcribing the holy works. According to illumination scholar John W. Bradley," As time goes on, after the tenth century, it is noticeable that the more beautiful a manuscript becomes in its writing the less accurate becomes its Latinity. And so the monks who once were noted for learning, gradually lose their grip on Latin. The manuscripts executed in Benedictine abbeys became inaccurate—almost illiterate. Faults of ignorance of words; misrendering of proper names; blundering in the inept introduction of marginal notes and confounding such notes with the text, showing that the heart of the copyist was not in his work nor his head capable of performing it. His hand is simply a machine, which when it goes wrong does so without remorse and without shame. "

The early Medieval illuminators favored morose and emaciated figures, hollowed cheeks and deep-set eyes, wide and feverish, filled with love for Christ. The miniature painting of the Irish, Gallic, and German monks was a melding together of painting and calligraphy. From the scrolls and flourishes purely calligraphic human forms are constructed. These early depictions were severe as judges with pitiless dignity, they stare from the pages like threatening tables of law, demanding submission, fear, and obedience, but according neither mercy, comfort, not redemption.

With the invention of the printing press, the art of manuscript illumination was doomed. What had once taken an illuminator a year of work could now be accomplished in a day.

The Meaning of Sacred Symbols in Paintings. Most prominently featured symbols and their meaning:

- The Serpent

- Good Shepherd

- Key

- Wheat

- Virgin Mary

- Christ

- The Anchor

- The Apostles

- Satan

- Chalice

- The Cross

- Fruit

- The Saints

- Colors

- Book

- Birds

- Angels

- Insects

- Fish

- Spider

- Animals

- Household Objects

Require more facts and information about Manuscript Illumination? Poke around every nook and cranny of the known universe for information this subject. Search Here

© HistoryofPainters.com If you like

this page and wish to share it, you are welcome to link to it, with our

thanks.

If you feel you have worthwhile information you would like to

contribute we would love to hear from you. We collect essential

biographical information and artist quotes from folks all over the

globe and appreciate your participation. When submitting please, if

possible, site the source and provide English translation. Email to

millardmulch@gmail.com